Solar households in Victoria, South Australia and New South Wales will this year cease to be paid for power they export into the electricity grid. In South Australia, some households will lose 16 cents per kilowatt-hour (c/kWh) from September 31. Some Victorian households will lose 25 c/kWh, and all NSW households will stop receiving payments from December 31.

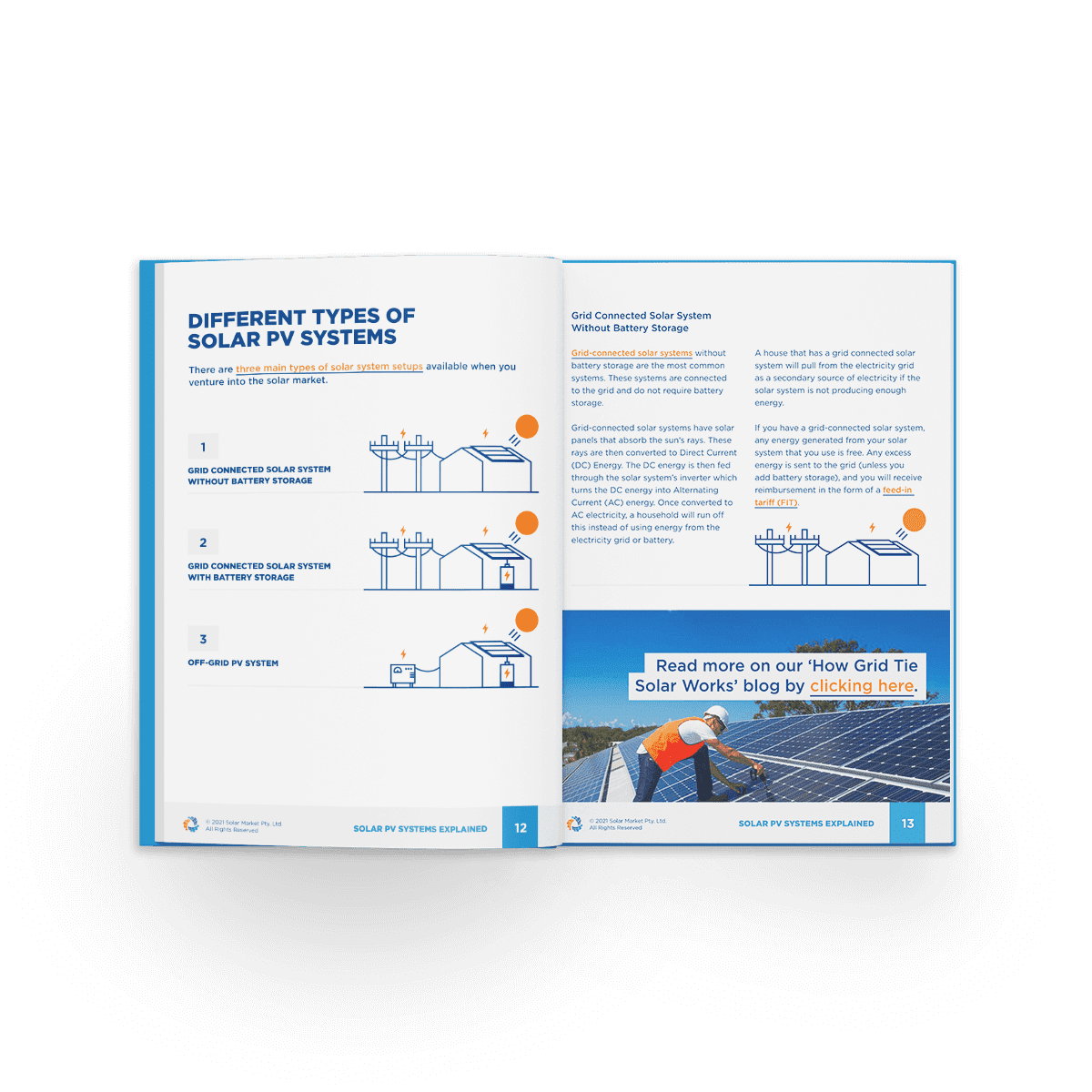

These “feed-in tariffs” were employed to kick-start the Australian solar photovoltaic (PV) industry. They offered high payments for electricity fed back into the grid from roof-mounted PV systems. These varied from state to state and time to time.

For many householders, these special tariffs are ending. Their feed-in tariffs will fall precipitously to 4-8 c/kWh, which is the typical rate available to new PV systems. In some cases households may lose over A$1,000 in income over a year.

But while the windback may hurt some households, it may ultimately be a good sign for the industry.

What can households do?

At present, householders with high feed-in tariffs are encouraged to export as much electricity to the grid as possible. These people will soon have an incentive to use this electricity and thereby displace expensive grid electricity. This will minimise loss of income.

Reverse-cycle air conditioning (for space heating and cooling) uses a lot of power that can be programmed to operate during daylight hours when solar panels are most likely to be generating electricity. The same applies to heating water, either by direct heating or through use of a heat pump. For heating water, solar PV is now competitive with gas, solar thermal and electricity from the grid.

Batteries, both stationary (for house services) and mobile (for electric cars), will also help control electricity use in the future.

A boost for the industry?

The ending of generous feed-in tariffs is likely to modestly encourage the solar PV industry. This is because many existing systems have a rating of only 1.5 kilowatts (kW), which could not have been increased without loss of the generous feed-in tariff.

Many householders will now choose to increase the size of their PV system to 5-10kW – in effect a new system given the disparity in average PV sizing between then and now.

A new large-scale PV market is also opening on commercial rooftops. Many businesses have daytime electrical needs that are better matched to solar availability than are domestic dwellings.

This allows businesses to consume the large amounts of the power their panels produce and hence minimise high commercial electricity tariffs. The constraining factors in this market are often not technical or economic, and include the fact that many businesses rent from landlords and tend to have short terms for investment. Business models are being developed to circumvent these constraints.

The rooftop PV market also now has large potential in competing with retail electricity prices. The total cost of a domestic 10kW PV system is about A$15,000. Over a 25-year lifetime this would yield an energy cost of 7 c/kWh.

This is about one-quarter of the typical Australian retail electricity tariff, about half of the off-peak electricity tariff, and similar to the typical retail gas tariff. Rooftop PV delivers energy services to the home more cheaply than anything else and has the capacity to drive natural gas out of domestic and commercial markets.

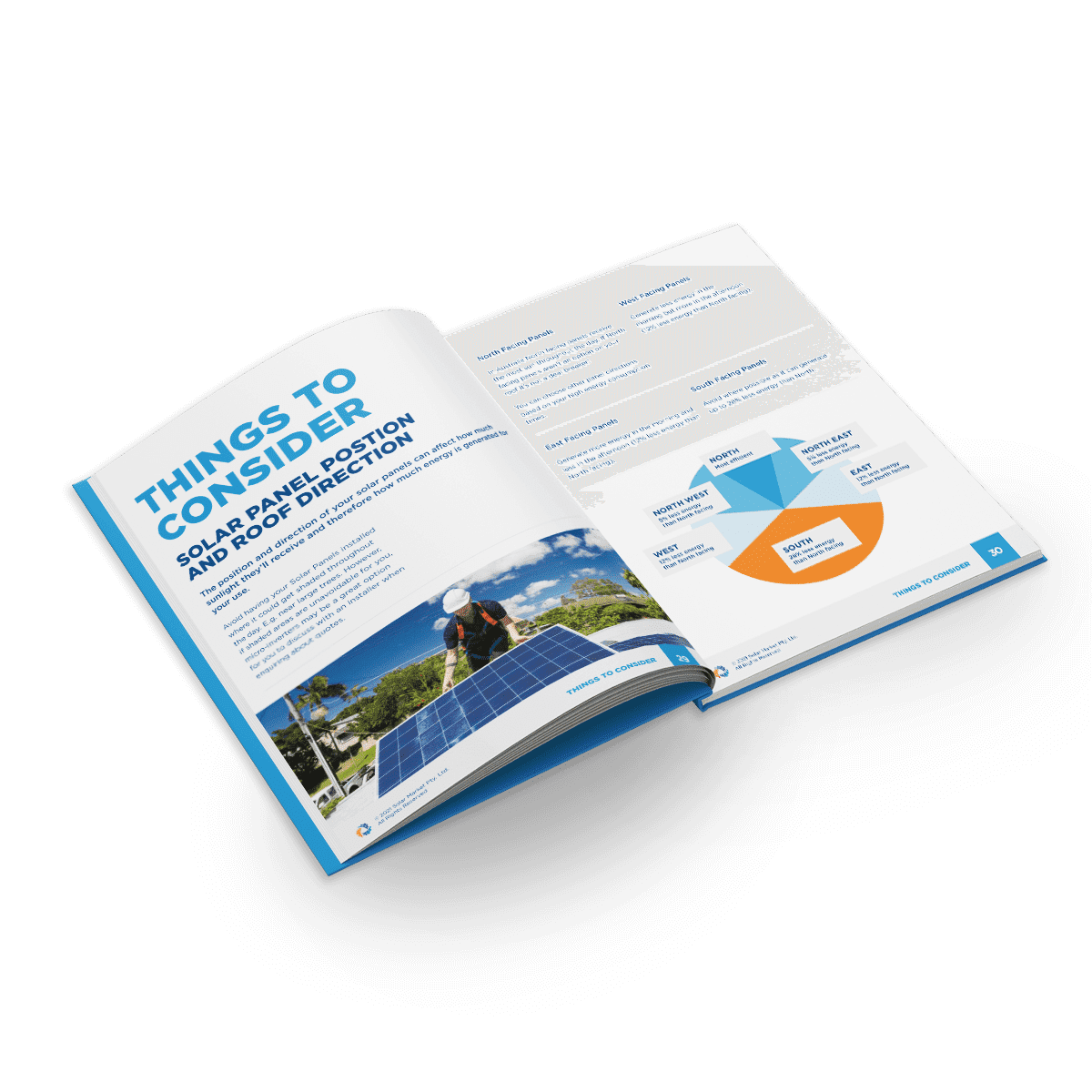

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, there are 9 million dwellings in Australia, and the floor area of new residential dwellings averaged 200 square metres over the past 20 years. Some of these dwellings are in multi-storey blocks, others have shaded roofs and, of course, south-facing roofs are less suitable than other orientations for PV.

However, if half the dwellings had one-third of their roofs covered in 20% efficient PV panels then 60 gigawatts (GW) could be accommodated. For perspective, this would cover 40% of Australian electricity demand. Commercial rooftops are a large additional market.

Solar getting big

Virtually all PV systems in Australia are roof-mounted. However, this is about to change because ground-mounted PV systems are becoming competitive with wind energy. We can see the falling cost of solar in the Queensland Solar 120 scheme, the Australian Capital Territory wind and PV reverse auctions and the Australian Renewable Energy Agency Large Scale Solar program , which all point to the declining cost of PV and wind.

Together, wind and PV constitute virtually all new generation capacity in Australia and half of the new generation capacity installed worldwide each year.

The total cost of a 10-50 megawatt PV system (1,000 times bigger than a 10kW system) is in the range A$2,100/kW (AC). A 25-year lifetime yields an energy cost of 8 c/kWh. This is only a little above the cost of wind energy and is fully competitive with new coal or gas generators.

Hundreds of 10-50MW PV systems can be distributed throughout sunny inland Australia close to towns and high-capacity powerlines. Australia’s 2020 renewable energy target is likely to be met with a large PV component, in addition to wind.

Wide distribution of PV and wind from north Queensland to Tasmania minimises the effect of local weather and takes full advantage of the complementary nature of the two leading renewable energy technologies.

The declining cost of PV and wind, coupled with the ready availability of pumped hydro storage, allows a high renewable electricity fraction (70-100%) to be achieved at modest cost by 2030.