The Australian government is reviewing our electricity market to make sure it can provide secure and reliable power in a rapidly changing world. Faced with the rise of renewable energy and limits on carbon pollution, The Conversation has asked experts what kind of future awaits the grid.

This year many Australian households will find themselves cut off from generous incentives paid for electricity they export into the grid from rooftop solar systems.

Between September and December, state feed-in tariff (FiT) schemes in New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia will finish. The FiTs applying to over 275,000 customers will drop from between 16 and 60 cents per kilowatt hour to between 5 and 7.2 cents per kWh. In NSW, the replacement FiT won’t be mandatory, with retailers allowed to decide what they pay. Of course, many of those customers have already recouped their investment.

Now that our rooftop solar industry has matured, we need to reconsider the purpose of FiTs and align them with our goals for the electricity system in the future.

Why pay solar households?

FiTs have been hugely important in getting the global solar industry to where it is now. Solar electricity costs have fallen to levels that were unimaginable just 10 years ago.

Governments have traditionally used FiTs to achieve a policy aim, such as increasing renewable energy production by bridging the gap between current costs of electricity and the cost of new sources.

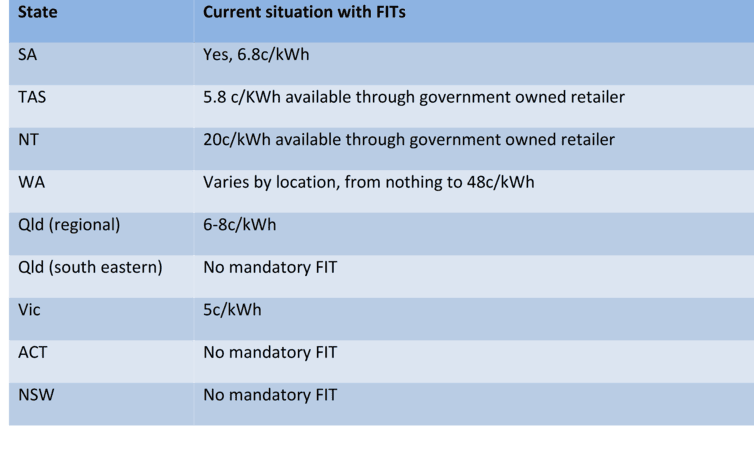

Australian states began to introduce mandated FiTs in 2008. There has never been a national FiT in Australia, and Queensland, NSW and the ACT no longer have mandated FiTs. However, many electricity retailers offer FiTs, even when not mandated by government.

The costs of FiTs are recovered in different ways, depending on whether they are government-mandated or not, but ultimately they fall on all electricity consumers. As governments wind back mandated FiTs, it’s assumed that FiTs will be roughly cost-neutral.

Have they worked?

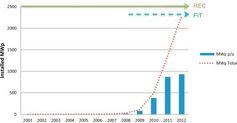

Residential solar installations soared after the introduction of FiTs in 2008. Installations quadrupled each year in Australia until 2012, leading to 11,600 jobs and the highest penetration of households with rooftop solar in the world.

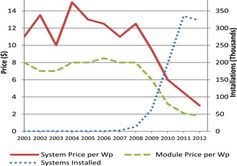

This boom stimulated a competitive solar market in which residential installation costs have plummeted (as you can see below). Australia now enjoys some of the lowest installation costs for rooftop solar in the world.

The trick that state policymakers missed, however, was making FiT policies sustainable.

Early FiTs were excessively high, especially in NSW and Queensland, causing policy fallout and sudden withdrawal. This was partly because the rapid reduction in solar prices exceeded expectations.

For example, the NSW government was forced into a hasty reassessment of its 2010 policy in order to prevent a cost blowout after massively underestimating the level of uptake. By October 2010, just 10 months after it began, the NSW gross FiT was slashed from 60 to 20 cents per kWh. The scheme was closed to new participants in April 2011.

Across Australia most states cut or entirely removed FiTs within four years. Most current FiTs are now well below retail prices. This means that customers are being encouraged to use as much as possible of their solar energy to power their own homes rather than exporting it to the grid. This is one of the reasons why the system size for solar installations in Australia tends to be smaller than elsewhere.

The fallout from these unsustainable FiT policies has unfortunately polarised the national conversation about solar. Hundreds of thousands of solar power system owners are facing bill shock as FiTs are withdrawn, while those who do not have solar have been told they are footing the bill for their neighbours’ systems.

Politicians have sought to capitalise on this discontent, by blaming solar tariffs for high electricity prices. In many states, the actual value of rooftop solar has been pushed out of the conversation.

The real value of solar

A recent Victorian report found that the value of solar energy depends on when electricity is fed into the grid. Solar energy is more valuable when exported to the grid at times of peak demand.

The report argued that the value of solar should account for the reduction in transmission losses (the losses associated with transporting electricity from large power plants over great distances) and environmental effects, primarily the reduction in greenhouse gases from displacing fossil fuel generation.

Solar installations can potentially add value in other ways too. For example, installing battery storage along with solar systems may allow domestic solar systems to offer other network services such as frequency and voltage control.

Encouragingly, since the report the Victorian government has bucked the national trend and announced a multi-rate FiT scheme.

The scheme offers different rates for exporting during peak, shoulder and off-peak times. It will also reward solar owners for the greenhouse gas offsets related to their system’s output. The scheme is expected to raise FiTs from around 5c per kWh to an average of between 6.5c and 7c per kWh.

What next?

Nationally, we need to refocus the conversation about the purpose and value of FiTs. Having already established a world-leading solar industry, we need to ask what FiTs can do for us now and into the future.

If we want our electricity system to take advantage of technological advances, such as battery storage, we need to repurpose our FiTs to reflect the benefits of these technologies. The Victorian example is a great step forward, providing a mechanism where consumers can leverage Australia’s low installation costs to become players in a more competitive energy market.

But there are even more benefits to distributed energy systems that could be realised with intelligently applied FiTs. This means we need more consideration of what solar systems can do for us, and less simplistic conversations about electricity costs.