The International Solar Alliance announced by India at the Paris climate conference invites together 120 countries to support the expansion of solar technologies in the developing world.

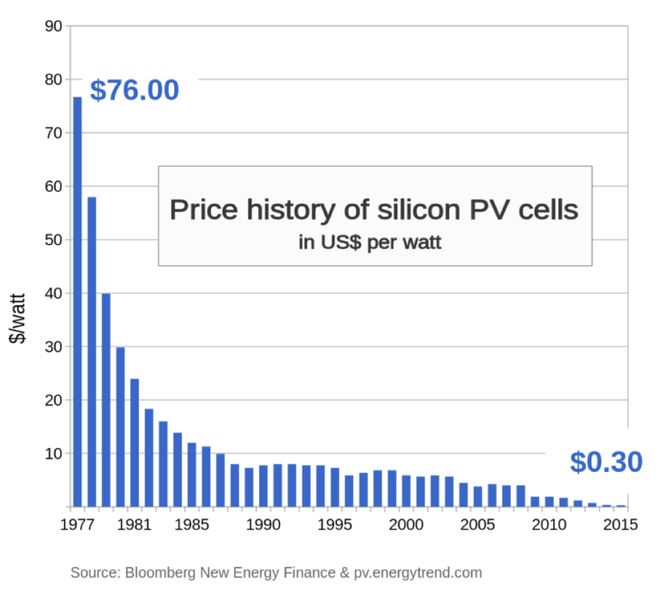

The cost of solar cells has decreased spectacularly over the past four decades, and the trend seems likely to continue. Solar energy has moved from a niche market for providing power in remote places (at the very beginning in 1958 to space satellites) to a mainstream technology which feeds into the national grid.

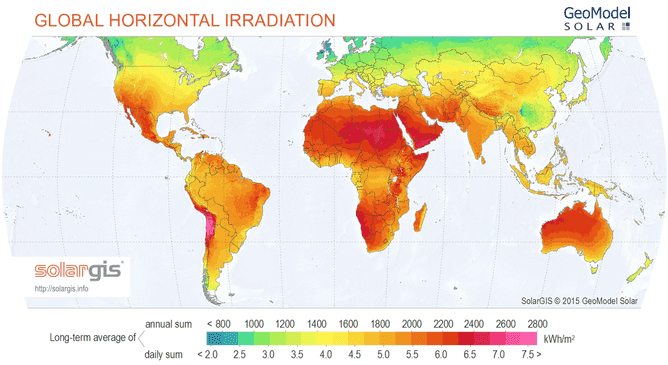

Most richer countries have been supporting solar power for some time and the rest of the world is now catching up, turning to solar not only for energy access in remote areas but to power cities. Emerging countries such as China, India, Brazil, Thailand, South Africa, Morocco or Egypt are investing in large solar plants with ambitious targets. In developing countries such as Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Kenya, Rwanda, Senegal or Ghana, solar farms or the large roll-out of solar home systems are a solution to unreliable and insufficient electricity supplies.

Large solar farms can be built in just a few months – compared to several years for a coal plant and even longer for a nuclear plant – without generating massive environmental and health damages. Modular decentralised generation with solar is a way to increase access to energy while still remaining on top of rapidly increasing appetites for electricity.

Culture of innovation

This alliance could boost the solar market in the Global South by accelerating the circulation of knowledge, facilitating technology transfer and securing investments. Such a partnership would aim to create a common culture among people working in solar energy. Permanent innovation is the key to success in a field where technologies evolve fast and where norms and standards are not yet established. So an alliance could help countries exchange policy ideas while benchmarking performance against each other.

Indeed in developing countries, where regulations and regimes tend to be less stable, investments suffer from a perceived risk. Given that the initial construction of solar plants makes up most of their cost (sunlight, after all, is free so ongoing expenses are minimal), the business model requires them to run for a long period. High risk means higher costs of financing the initial investment. Countries with well-designed regulatory frameworks and policies can reduce risk and attract investors.

The alliance could also support a network of universities and local research centres in each country to capitalise on local experience and build knowledge. Research and development can then more easily target the specific needs of developing countries.

… and the real politics of renewables

The intensification of globalisation and competition between technology firms and utilities is sparking a revolution in the electricity sector which could result in a new world of energy providers. A number of countries are keen to position themselves as leaders.

For the moment, both China and India want massive investments in solar only on top of further investments in new coal and gas plants. They need to make their growth less carbon intensive – but do not yet consider solar power as a complete substitute for fossil fuels.

But renewables accounted for nearly half of all new power generation capacity across the world last year. As the cost of solar power is falling to the same level as traditional energy supplies all over the world, some players in the electricity sector are – willingly or not – shifting away from fossil fuels. The decarbonisation of the electricity sector may be not just an empty political pledge, but an economic necessity.

Xavier Lemaire, Senior Research Associate, Energy Institute, UCL

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.