Gordon Weiss, University of Sydney

The resumed growth of Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions after almost a decade of consistent decline shows the scale of the challenge ahead if Australia is to meet its climate commitments.

This week’s RepuTex analysis forecasts that national emissions will rise 6% by 2020, with no peak in sight until 2030. The signs are that the uptick for 2014-15 marks a reversal of the recent downward trend proclaimed by federal environment minister Greg Hunt.

With the world’s nations having pledged in Paris to limit global warming to well below 2℃, it is clear that Australia (which joined the “high-ambition” diplomatic push for a 1.5℃ target also to be included in the agreement), will be expected to make far deeper emissions cuts than it has so far achieved.

Emissions on the rise

December’s federal government update of Australia’s emissions showed that emissions for 2014-15 did not rise dramatically from previous years, but it also highlighted two key considerations.

One, for the first time in almost a decade, Australia’s emissions did not fall from one year to the next. And two, the volume of electricity generated in the National Electricity Market also failed to fall. As electricity generation is responsible for one-third of Australia’s emissions, an increase in electricity is likely to drive up emissions overall.

Also in December, the government updated its forecast of national emissions out to 2020, which contained both good and bad news. The good news is that under the rules defined by the Kyoto Protocol, Australia’s rising emissions won’t stop it from meeting its cumulative 2020 emissions obligations. The bad news is that Australia is not on track to achieve its absolute emissions reduction target of 5% below 2000 levels by 2020.

Current policies can do the job

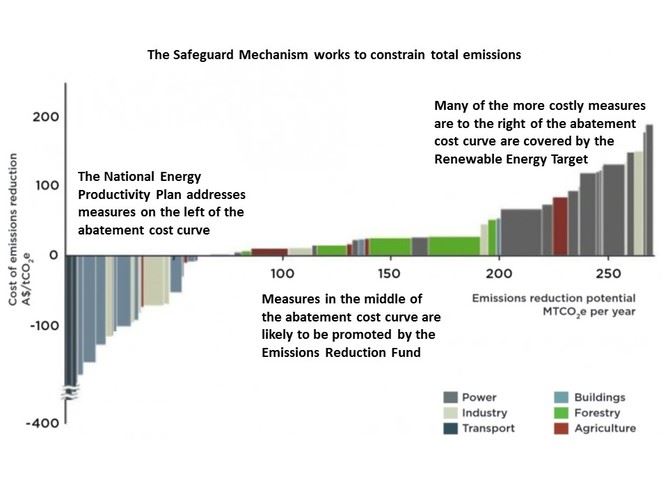

Clearly Australia needs to turn things around. But there is good news here too, because it already has a broad suite of policies that can cut greenhouse gas emissions. Among them is the newly released National Energy Productivity Plan (NEPP), as well as the Renewable Energy Target (RET), the Emissions Reduction Fund (ERF) (which may yet receive a funding boost), and the Safeguard Mechanism, which comes into force later this year and is designed to ensure that big emitters don’t wipe out the emissions savings made by projects funded under the ERF.

Some measures to cut emissions are more cost-effective than others – replacing power infrastructure is expensive, for instance, while improving fuel efficiency actually saves money. Different economic sectors can thus be plotted on an emissions-reduction “cost curve”, as seen below.

Here’s how the various existing policies can each make a significant contribution.

Energy productivity

Looking at the cost curve, we see that some of cheapest emissions reductions can be found in saving energy. As Australia’s energy productivity lags other G20 countries, the NEPP can drive both emissions reductions and deliver broad economic benefits by maximising the value derived from each unit of energy. The sooner we see key parts of the NEPP implemented, such as requirements for light vehicle fuel efficiency, the greater its impact on emissions.

Emissions Reduction Fund

Judging by the two ERF auctions held so far, it seems that the scheme will mainly encourage projects such as low-emission farming and land use changes. The Paris climate agreement called for nations to embrace their “common and differentiated responsibilities”, and land use is surely one sector where Australia has greater potential than many countries to cut emissions.

Renewable Energy Target

The RET has made inroads into decarbonising electricity generation without drawing funds from other programs. While economic purists argue against promoting low-carbon electricity ahead of cheaper emissions-reduction measures, the RET is crucial for delivering on the long-term need to decarbonise the power sector.

The author’s own analysis of the interaction between the NEPP and the RET demonstrates how these policies complement each other, as improved energy efficiency and the growth in renewables both reduce the demand for electricity from coal-fired power stations. Weaning ourselves off coal will be essential if we hope to achieve deeper cuts to emissions.

The Safeguard Mechanism

During the Paris climate talks, Hunt acknowledged what commentators had been saying for some time: that the Safeguard Mechanism, aimed at constraining Australia’s largest emitters, has many of the features of a baseline-and-credit carbon trading scheme, and can drive emissions reductions.

Emitters will only be penalised when emissions exceed their agreed baseline, thus reducing the scheme’s overall economic impact. This allows for a much sharper price signal when emissions are excessive, and can reward the best performers. Furthermore, the Safeguard Mechanism will generate demand for emissions reduction activities across the whole economy, beyond the projects directly funded by the ERF.

An end to uncertainty?

In the wake of the Paris climate deal, the International Monetary Fund issued a statement saying that it was essential to price emissions. With the Safeguard Mechanism set to establish a market for emissions reductions, working together with other climate change policies, perhaps Australia now has a set of complementary policies that can help restore some certainty to its response to climate change.

We just need to move quickly and in step with the rest of the world.

![]()

Gordon Weiss, Honorary Associate, School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, University of Sydney

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.