The governing body for our energy market, the Australian Energy Market Commission, has just missed a major opportunity to modernise our electricity networks. Last week the commission rejected a proposal to pay credits to small, local generators (such as small wind, solar and gas). Our research shows that this could save electricity consumers A$1.2 billion by 2050.

In July 2015, the City of Sydney, Total Environment Centre and NSW Property Council proposed the Local Generation Network Credit rule change. This would have required network businesses to pay a credit for electricity exported into the distribution grid – that is, close to where it is actually consumed.

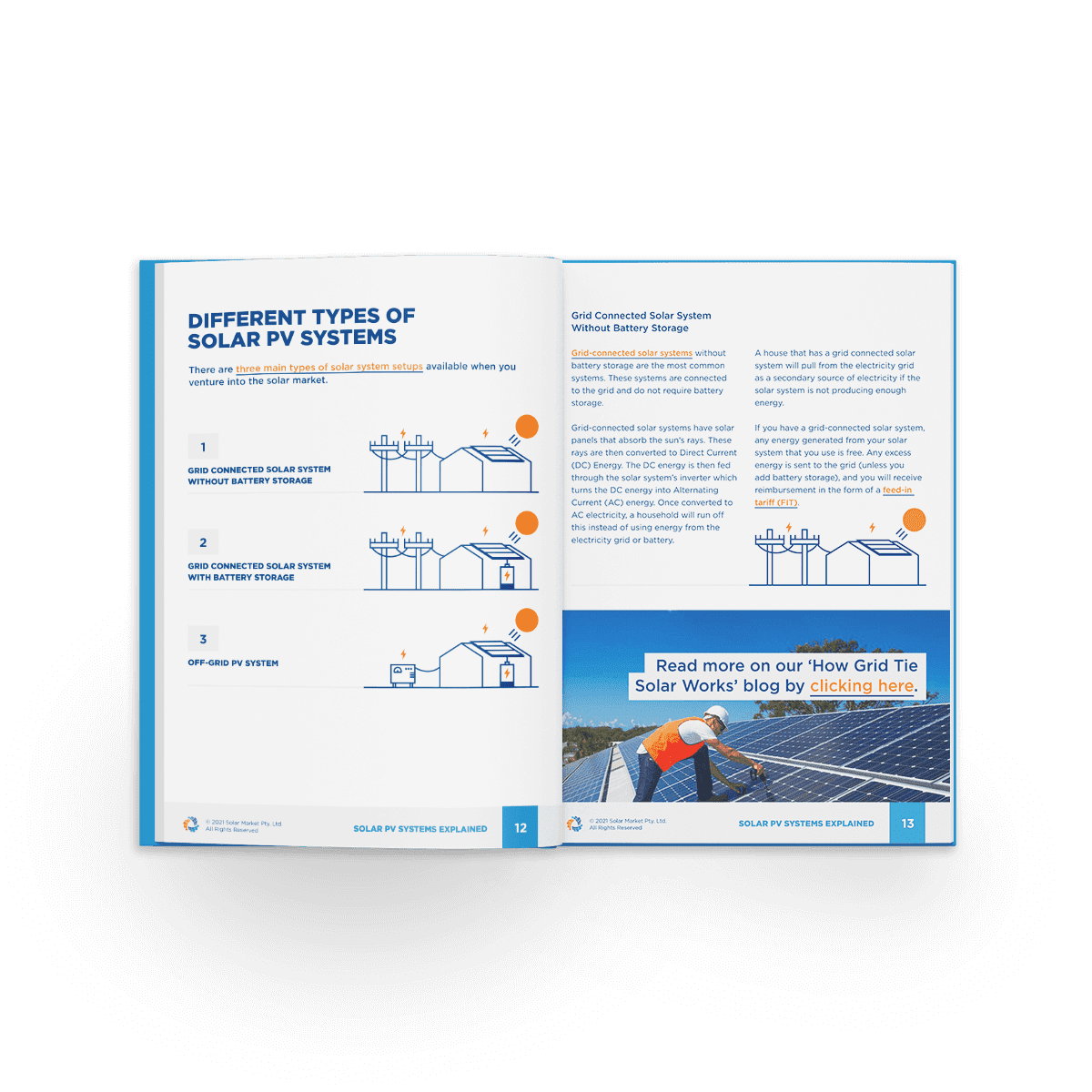

This is different to the credit (known as a “feed-in tariff”, or FIT) paid by electricity retailers for solar households that export power, which reflects the energy value of the solar rather than any network value. FITs are a fixed payment for the amount of power exported with no variation for the time of day. In most states, retailer FITs have replaced generous mandatory FITs set by state governments, and usually have an upper limit on system size somewhere between 5 and 100 kilowatts.

The network rule change would have been a small but crucial step towards recognising that in the future electricity will flow both to and from consumers, as more and more individuals, communities and businesses install their own generation.

It is just one of the rule changes needed to make an orderly, efficient transition, rather than a cycle where consumers get more and more frustrated as they are forced into workarounds to deal with outdated regulations, and regulators and markets play catch-up.

The cost of connection

About half of our electricity prices are made up of network charges. These cover the cost of building and maintaining the poles and wires that get electricity from generators to our homes and businesses. Traditionally, that was a long way, as electricity all came from large centralised generators.

This is all changing, as homes and businesses increasingly install their own solar, wind or gas generators. These trends are being driven by the increase in electricity prices, cost reductions in renewable energy, and a range of other motives such as climate targets, aspirations for self-sufficiency, and wishing to take control of energy spending.

Network costs have been the main contributor to a big jump in Australian electricity prices over the last 15 years. There was a huge investment to cope with the projected rise in electricity demand, which has so far failed to happen.

Described as “gold plating”, it would have been smarter and cheaper to do a whole mix of other things – energy efficiency, local generation and so on – instead of the big investment focused on network infrastructure.

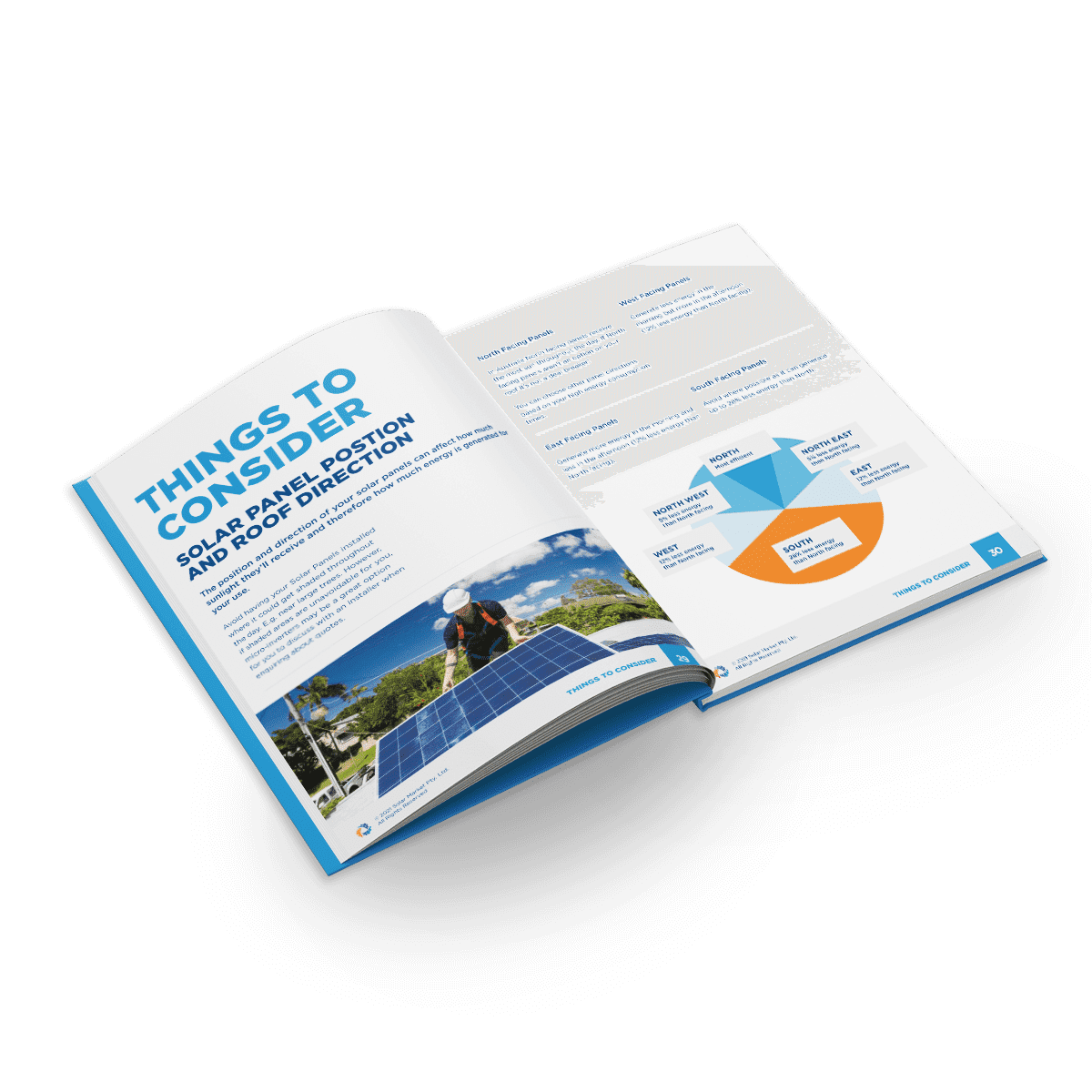

Because the electricity from local generators is used physically close to where it is generated, it reduces congestion on the network and so can reduce the need to upgrade. The proposed rule change is aimed at rewarding local generators for export at peak times, when the network is under most strain, and so avoiding the long-term need for network investment.

The rule change would also enable many local generation projects, and keep them using the network to share energy. Without this incentive most generators will use their energy onsite rather than exporting to the grid.

This gets the biggest return, as it means each unit you generate avoids the entire volume charge of a unit imported from the grid.

Consumers lose out

But what if you have several buildings and want to generate at one and use it at the other? Tough luck.

Unless you can connect those buildings with a private wire – instead of connecting them via the grid – it’s unlikely to be economic. Consumers pay the same network charges whether the energy is transported across the road or halfway across the state.

This rule change would have meant that you got a network credit for the generation, and therefore helped reduce what you pay to use the network. It would be a win-win for everyone, as putting in a private wire is just duplication of the network that already exists and makes everyone – the network business, the organisation and, by implication, other consumers – worse off.

Of course, a private wire isn’t possible in all situations, but the principle remains: the local network credit offers an alternative to behind-the-meter generation.

The Institute for Sustainable Futures recently led a year-long project looking at local generation network credits and local electricity trading. The results showed pretty clearly that, if designed well, this rule change would be good for local energy projects and good for electricity consumers.

As a result of the economic modelling, we recommended that existing systems and all small (less than 10 kilowatt) systems do not receive the network credit, in order to maximise benefits for everyone. The payments are unlikely to make a difference to whether those small systems go in, and paying them the credit would means an overall cost, rather than a long-term benefit of A$1.2 billion for everyone.

This was a change from the original proposal and was presented to the AEMC in great detail. The rule change proponents were also quite happy with these limits being imposed.

So what did the AEMC decide?

The AEMC considers rule change proposals – and accepts, rejects, or makes what is called a “preferred rule”. It is a very arcane process, with little scope for collaborative outcomes.

On this issue, the AEMC delivered a “preferred rule” – which does nothing to solve the problem. The commission ignored the opportunity to work with stakeholders to deliver an alternative rule that would benefit both local projects and all consumers.

Instead, it proposes that network businesses be required to provide information on upcoming constraints, including a dollar value for alternatives to network investment. That’s all well and good, except that the information is already available in the form of Network Opportunity Maps.

Unfortunately it’s just more evidence that the AEMC has lost touch with what is actually happening in the market, and with what consumers want.

So where to now? There is a six-week consultation period on the draft rule – and we can only hope that the AEMC reconsiders its decision.