Debunking the Myth: Wind Energy Not to Blame for South Australia’s Electricity Price Spikes

The past three weeks have seen considerable discussion of Australia’s wholesale electricity market, driven largely by severe price spikes in South Australia. Hugh Saddler, writing last week on The Conversation, and the Climate Council, in a report, have each done a good job of busting the myth that this is all because of SA’s relatively large share of wind energy.

After outlining the growing lack of competitiveness in the SA electricity sector, Saddler called for “a fundamental rethink” of the National Electricity Market (NEM). What would this involve?

Wholesale prices

Wholesale electricity prices are determined for each half hour, and in the NEM are capped at A$14,000 per megawatt hour. Prices very rarely hit these stratospheric levels and, in any event, the wholesale price spikes do not directly or immediately filter down to households and other small consumers. However, industrial customers are beginning to complain about the strain.

One factor that seems largely to have escaped comment is that temporary high prices are a deliberate design feature of our electricity market. Occasional price spikes are precisely how the market attracts new investment, because in theory high prices represent tightening supply and therefore signal a gap in the market for new generators.

Certainly, this isn’t the only time that prices have spiked. In response to high prices in South Australia in 2008 (before most of the state’s wind farms were built), industrial consumers tried unsuccessfully to introduce rules preventing certain generators putting high price bids into the market. More recently, Queensland saw high prices in the summer of 2014-15, as did Tasmania earlier this year.

A market in transition

But while price spikes are neither unprecedented nor unexpected, there are nevertheless changes afoot in the electricity sector. The falling cost of renewable energy, and policies such as the federal Renewable Energy Target (and similar state and territory schemes), are encouraging new entrants into the market.

With one of the most emissions-intensive electricity sectors in the world and an ageing fleet of coal-fired power stations, traditional generators are spending increasing amounts on maintenance, upgrades and closures.

Wind and large-scale solar, meanwhile, are now the cheapest new-build generation technologies. This promises to turn the energy market on its head.

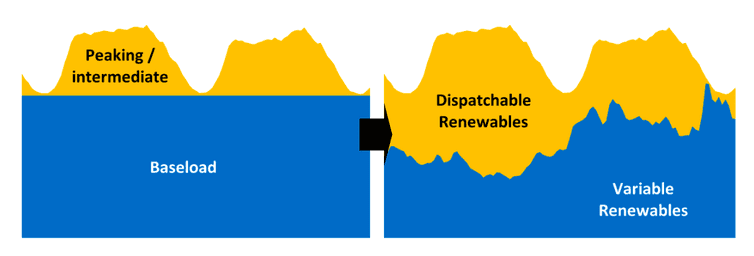

UNSW research on the implications of moving to 100% renewables has shown that to do so we will eventually need to ditch the idea of “baseload generation” (as delivered by 20th-century thermal power stations) in favour of “peaking generation” that is more responsive to changes in supply.

This might mean using a mixture of renewables such as solar and wind, backed up by gas-fired power stations that can be rapidly switched on and off, as well as “dispatchable” energy solutions such as storage, bioenergy and concentrating solar thermal.

As seen in the chart below, sourced from the UNSW report, with enough rapid-response options built into the system, traditional baseload generators would not be needed at all.

Obviously, moving seamlessly to this new approach will require changes to the way the market is run. One option might be to change the pricing window from 30 minutes to five minutes, which could entice a wider range of participants into the market.

Other fundamental changes also need to be made. Three deserve particular consideration:

- incentivising dispatchable energy solutions to enter the market;

- increasing access to markets for decentralised energy; and

- increasing the alignment between energy and environmental considerations.

Dispatchable energy

Besides “traditional” renewables such as wind and solar farms, renewable energy schemes could specifically tender for “dispatchable” solutions such as demand management, concentrated solar thermal, sustainable bioenergy or storage. The SA government announced plans to do just this, by targeting these solutions for 25% of the government’s energy use.

If this is to happen more broadly, it should be done in alignment with the outcomes of the reviews that the Australian Energy Market Commission and the Australian Market Operator are undertaking on the security of the market.

Decentralised energy

One of the most exciting areas of investment in the NEM over the past decade has been the hundreds of thousands of homes installing their own solar systems. Technologies such as batteries, smart homes and improved load management mean that individual consumers are increasingly willing and able to get involved with the energy market, rather than just being consumers.

Yet the link to wholesale electricity markets is currently just as tenuous for a small generator as it is for a small consumer. Any market reform must therefore ensure that groupings of such small-scale producers can supply the market’s needs in a meaningful way.

For inspiration we can look to New York state, which is designing an energy market geared towards decentralised options such as solar panels. To encourage decentralised systems, New York is embarking on the Reforming Energy Vision plan to lower the financial and environmental costs of power and make the market more resilient.

Environment and energy

Energy and environment policies have been too separate for too long, which is why the appointment of a single federal environment and energy minister is a welcome move.

However, the National Electricity Objective, which forms the basis of energy policy decisions, does not include an environmental component. It emphasises “price, quality, safety, reliability and security”, but not emissions. This means that regulators cannot consider the climate or environmental implications of their decisions.

Unless the objective is amended, we are likely to see perverse outcomes of energy decisions. One previous example was the four-year delay in introducing the Demand Management Incentive Scheme, despite the fact that it is likely to save money and cut carbon emissions.

With Australia’s electricity at a technological crossroads, it is important that we make sure we are going in the right direction.